Welcome to the HPX documentation!¶

If you’re new to HPX you can get started with the Quick start guide. Don’t forget to read the Terminology section to learn about the most important concepts in HPX. The Examples give you a feel for how it is to write real HPX applications and the Manual contains detailed information about everything from building HPX to debugging it. There are links to blog posts and videos about HPX in Additional material.

If you can’t find what you’re looking for in the documentation, please:

open an issue on GitHub;

contact us on IRC, the HPX channel on the C++ Slack, or on our mailing list; or

read or ask questions tagged with HPX on StackOverflow.

See Citing HPX for details on how to cite HPX in publications. See HPX users for a list of institutions and projects using HPX.

What is HPX?¶

HPX is a C++ Standard Library for Concurrency and Parallelism. It implements all of the corresponding facilities as defined by the C++ Standard. Additionally, in HPX we implement functionalities proposed as part of the ongoing C++ standardization process. We also extend the C++ Standard APIs to the distributed case. HPX is developed by the STE||AR group (see People).

The goal of HPX is to create a high quality, freely available, open source implementation of a new programming model for conventional systems, such as classic Linux based Beowulf clusters or multi-socket highly parallel SMP nodes. At the same time, we want to have a very modular and well designed runtime system architecture which would allow us to port our implementation onto new computer system architectures. We want to use real-world applications to drive the development of the runtime system, coining out required functionalities and converging onto a stable API which will provide a smooth migration path for developers.

The API exposed by HPX is not only modeled after the interfaces defined by the C++11/14/17/20 ISO standard. It also adheres to the programming guidelines used by the Boost collection of C++ libraries. We aim to improve the scalability of today’s applications and to expose new levels of parallelism which are necessary to take advantage of the exascale systems of the future.

What’s so special about HPX?¶

HPX exposes a uniform, standards-oriented API for ease of programming parallel and distributed applications.

It enables programmers to write fully asynchronous code using hundreds of millions of threads.

HPX provides unified syntax and semantics for local and remote operations.

HPX makes concurrency manageable with dataflow and future based synchronization.

It implements a rich set of runtime services supporting a broad range of use cases.

HPX exposes a uniform, flexible, and extendable performance counter framework which can enable runtime adaptivity

It is designed to solve problems conventionally considered to be scaling-impaired.

HPX has been designed and developed for systems of any scale, from hand-held devices to very large scale systems.

It is the first fully functional implementation of the ParalleX execution model.

HPX is published under a liberal open-source license and has an open, active, and thriving developer community.

Why HPX?¶

Current advances in high performance computing (HPC) continue to suffer from the issues plaguing parallel computation. These issues include, but are not limited to, ease of programming, inability to handle dynamically changing workloads, scalability, and efficient utilization of system resources. Emerging technological trends such as multi-core processors further highlight limitations of existing parallel computation models. To mitigate the aforementioned problems, it is necessary to rethink the approach to parallelization models. ParalleX contains mechanisms such as multi-threading, parcels, global name space support, percolation and local control objects (LCO). By design, ParalleX overcomes limitations of current models of parallelism by alleviating contention, latency, overhead and starvation. With ParalleX, it is further possible to increase performance by at least an order of magnitude on challenging parallel algorithms, e.g., dynamic directed graph algorithms and adaptive mesh refinement methods for astrophysics. An additional benefit of ParalleX is fine-grained control of power usage, enabling reductions in power consumption.

ParalleX—a new execution model for future architectures¶

ParalleX is a new parallel execution model that offers an alternative to the conventional computation models, such as message passing. ParalleX distinguishes itself by:

Split-phase transaction model

Message-driven

Distributed shared memory (not cache coherent)

Multi-threaded

Futures synchronization

Synchronization for anonymous producer-consumer scenarios

Percolation (pre-staging of task data)

The ParalleX model is intrinsically latency hiding, delivering an abundance of variable-grained parallelism within a hierarchical namespace environment. The goal of this innovative strategy is to enable future systems delivering very high efficiency, increased scalability and ease of programming. ParalleX can contribute to significant improvements in the design of all levels of computing systems and their usage from application algorithms and their programming languages to system architecture and hardware design together with their supporting compilers and operating system software.

What is HPX?¶

High Performance ParalleX (HPX) is the first runtime system implementation of the ParalleX execution model. The HPX runtime software package is a modular, feature-complete, and performance-oriented representation of the ParalleX execution model targeted at conventional parallel computing architectures, such as SMP nodes and commodity clusters. It is academically developed and freely available under an open source license. We provide HPX to the community for experimentation and application to achieve high efficiency and scalability for dynamic adaptive and irregular computational problems. HPX is a C++ library that supports a set of critical mechanisms for dynamic adaptive resource management and lightweight task scheduling within the context of a global address space. It is solidly based on many years of experience in writing highly parallel applications for HPC systems.

The two-decade success of the communicating sequential processes (CSP) execution model and its message passing interface (MPI) programming model have been seriously eroded by challenges of power, processor core complexity, multi-core sockets, and heterogeneous structures of GPUs. Both efficiency and scalability for some current (strong scaled) applications and future Exascale applications demand new techniques to expose new sources of algorithm parallelism and exploit unused resources through adaptive use of runtime information.

The ParalleX execution model replaces CSP to provide a new computing paradigm embodying the governing principles for organizing and conducting highly efficient scalable computations greatly exceeding the capabilities of today’s problems. HPX is the first practical, reliable, and performance-oriented runtime system incorporating the principal concepts of the ParalleX model publicly provided in open source release form.

HPX is designed by the STE||AR Group (Systems Technology, Emergent Parallelism, and Algorithm Research) at Louisiana State University (LSU)’s Center for Computation and Technology (CCT) to enable developers to exploit the full processing power of many-core systems with an unprecedented degree of parallelism. STE||AR is a research group focusing on system software solutions and scientific application development for hybrid and many-core hardware architectures.

What makes our systems slow?¶

Estimates say that we currently run our computers at well below 100% efficiency. The theoretical peak performance (usually measured in FLOPS—floating point operations per second) is much higher than any practical peak performance reached by any application. This is particularly true for highly parallel hardware. The more hardware parallelism we provide to an application, the better the application must scale in order to efficiently use all the resources of the machine. Roughly speaking, we distinguish two forms of scalability: strong scaling (see Amdahl’s Law) and weak scaling (see Gustafson’s Law). Strong scaling is defined as how the solution time varies with the number of processors for a fixed total problem size. It gives an estimate of how much faster we can solve a particular problem by throwing more resources at it. Weak scaling is defined as how the solution time varies with the number of processors for a fixed problem size per processor. In other words, it defines how much more data can we process by using more hardware resources.

In order to utilize as much hardware parallelism as possible an application must exhibit excellent strong and weak scaling characteristics, which requires a high percentage of work executed in parallel, i.e., using multiple threads of execution. Optimally, if you execute an application on a hardware resource with N processors it either runs N times faster or it can handle N times more data. Both cases imply 100% of the work is executed on all available processors in parallel. However, this is just a theoretical limit. Unfortunately, there are more things that limit scalability, mostly inherent to the hardware architectures and the programming models we use. We break these limitations into four fundamental factors that make our systems SLOW:

Starvation occurs when there is insufficient concurrent work available to maintain high utilization of all resources.

Latencies are imposed by the time-distance delay intrinsic to accessing remote resources and services.

Overhead is work required for the management of parallel actions and resources on the critical execution path, which is not necessary in a sequential variant.

Waiting for contention resolution is the delay due to the lack of availability of oversubscribed shared resources.

Each of those four factors manifests itself in multiple and different ways; each of the hardware architectures and programming models expose specific forms. However, the interesting part is that all of them are limiting the scalability of applications no matter what part of the hardware jungle we look at. Hand-helds, PCs, supercomputers, or the cloud, all suffer from the reign of the 4 horsemen: Starvation, Latency, Overhead, and Contention. This realization is very important as it allows us to derive the criteria for solutions to the scalability problem from first principles, and it allows us to focus our analysis on very concrete patterns and measurable metrics. Moreover, any derived results will be applicable to a wide variety of targets.

Technology demands new response¶

Today’s computer systems are designed based on the initial ideas of John von Neumann, as published back in 1945, and later extended by the Harvard architecture. These ideas form the foundation, the execution model, of computer systems we use currently. However, a new response is required in the light of the demands created by today’s technology.

So, what are the overarching objectives for designing systems allowing for applications to scale as they should? In our opinion, the main objectives are:

Performance: as previously mentioned, scalability and efficiency are the main criteria people are interested in.

Fault tolerance: the low expected mean time between failures (MTBF) of future systems requires embracing faults, not trying to avoid them.

Power: minimizing energy consumption is a must as it is one of the major cost factors today, and will continue to rise in the future.

Generality: any system should be usable for a broad set of use cases.

Programmability: for programmer this is a very important objective, ensuring long term platform stability and portability.

What needs to be done to meet those objectives, to make applications scale better on tomorrow’s architectures? Well, the answer is almost obvious: we need to devise a new execution model—a set of governing principles for the holistic design of future systems—targeted at minimizing the effect of the outlined SLOW factors. Everything we create for future systems, every design decision we make, every criteria we apply, have to be validated against this single, uniform metric. This includes changes in the hardware architecture we prevalently use today, and it certainly involves new ways of writing software, starting from the operating system, runtime system, compilers, and at the application level. However, the key point is that all those layers have to be co-designed; they are interdependent and cannot be seen as separate facets. The systems we have today have been evolving for over 50 years now. All layers function in a certain way, relying on the other layers to do so. But we do not have the time to wait another 50 years for a new coherent system to evolve. The new paradigms are needed now—therefore, co-design is the key.

Governing principles applied while developing HPX¶

As it turn out, we do not have to start from scratch. Not everything has to be invented and designed anew. Many of the ideas needed to combat the 4 horsemen already exist, many for more than 30 years. All it takes is to gather them into a coherent approach. We’ll highlight some of the derived principles we think to be crucial for defeating SLOW. Some of those are focused on high-performance computing, others are more general.

Focus on latency hiding instead of latency avoidance¶

It is impossible to design a system exposing zero latencies. In an effort to come as close as possible to this goal many optimizations are mainly targeted towards minimizing latencies. Examples for this can be seen everywhere, such as low latency network technologies like InfiniBand, caching memory hierarchies in all modern processors, the constant optimization of existing MPI implementations to reduce related latencies, or the data transfer latencies intrinsic to the way we use GPGPUs today. It is important to note that existing latencies are often tightly related to some resource having to wait for the operation to be completed. At the same time it would be perfectly fine to do some other, unrelated work in the meantime, allowing the system to hide the latencies by filling the idle-time with useful work. Modern systems already employ similar techniques (pipelined instruction execution in the processor cores, asynchronous input/output operations, and many more). What we propose is to go beyond anything we know today and to make latency hiding an intrinsic concept of the operation of the whole system stack.

Embrace fine-grained parallelism instead of heavyweight threads¶

If we plan to hide latencies even for very short operations, such as fetching the contents of a memory cell from main memory (if it is not already cached), we need to have very lightweight threads with extremely short context switching times, optimally executable within one cycle. Granted, for mainstream architectures, this is not possible today (even if we already have special machines supporting this mode of operation, such as the Cray XMT). For conventional systems, however, the smaller the overhead of a context switch and the finer the granularity of the threading system, the better will be the overall system utilization and its efficiency. For today’s architectures we already see a flurry of libraries providing exactly this type of functionality: non-pre-emptive, task-queue based parallelization solutions, such as Intel Threading Building Blocks (TBB), Microsoft Parallel Patterns Library (PPL), Cilk++, and many others. The possibility to suspend a current task if some preconditions for its execution are not met (such as waiting for I/O or the result of a different task), seamlessly switching to any other task which can continue, and to reschedule the initial task after the required result has been calculated, which makes the implementation of latency hiding almost trivial.

Rediscover constraint-based synchronization to replace global barriers¶

The code we write today is riddled with implicit (and explicit) global barriers. By “global barriers,” we mean the synchronization of the control flow between several (very often all) threads (when using OpenMP) or processes (MPI). For instance, an implicit global barrier is inserted after each loop parallelized using OpenMP as the system synchronizes the threads used to execute the different iterations in parallel. In MPI each of the communication steps imposes an explicit barrier onto the execution flow as (often all) nodes have to be synchronized. Each of those barriers is like the eye of a needle the overall execution is forced to be squeezed through. Even minimal fluctuations in the execution times of the parallel threads (jobs) causes them to wait. Additionally, it is often only one of the executing threads that performs the actual reduce operation, which further impedes parallelism. A closer analysis of a couple of key algorithms used in science applications reveals that these global barriers are not always necessary. In many cases it is sufficient to synchronize a small subset of the threads. Any operation should proceed whenever the preconditions for its execution are met, and only those. Usually there is no need to wait for iterations of a loop to finish before you can continue calculating other things; all you need is to complete the iterations that produce the required results for the next operation. Good bye global barriers, hello constraint based synchronization! People have been trying to build this type of computing (and even computers) since the 1970s. The theory behind what they did is based on ideas around static and dynamic dataflow. There are certain attempts today to get back to those ideas and to incorporate them with modern architectures. For instance, a lot of work is being done in the area of constructing dataflow-oriented execution trees. Our results show that employing dataflow techniques in combination with the other ideas, as outlined herein, considerably improves scalability for many problems.

Adaptive locality control instead of static data distribution¶

While this principle seems to be a given for single desktop or laptop computers (the operating system is your friend), it is everything but ubiquitous on modern supercomputers, which are usually built from a large number of separate nodes (i.e., Beowulf clusters), tightly interconnected by a high-bandwidth, low-latency network. Today’s prevalent programming model for those is MPI, which does not directly help with proper data distribution, leaving it to the programmer to decompose the data to all of the nodes the application is running on. There are a couple of specialized languages and programming environments based on PGAS (Partitioned Global Address Space) designed to overcome this limitation, such as Chapel, X10, UPC, or Fortress. However, all systems based on PGAS rely on static data distribution. This works fine as long as this static data distribution does not result in heterogeneous workload distributions or other resource utilization imbalances. In a distributed system these imbalances can be mitigated by migrating part of the application data to different localities (nodes). The only framework supporting (limited) migration today is Charm++. The first attempts towards solving related problem go back decades as well, a good example is the Linda coordination language. Nevertheless, none of the other mentioned systems support data migration today, which forces the users to either rely on static data distribution and live with the related performance hits or to implement everything themselves, which is very tedious and difficult. We believe that the only viable way to flexibly support dynamic and adaptive locality control is to provide a global, uniform address space to the applications, even on distributed systems.

Prefer moving work to the data over moving data to the work¶

For the best performance it seems obvious to minimize the amount of bytes transferred from one part of the system to another. This is true on all levels. At the lowest level we try to take advantage of processor memory caches, thus, minimizing memory latencies. Similarly, we try to amortize the data transfer time to and from GPGPUs as much as possible. At high levels we try to minimize data transfer between different nodes of a cluster or between different virtual machines on the cloud. Our experience (well, it’s almost common wisdom) shows that the amount of bytes necessary to encode a certain operation is very often much smaller than the amount of bytes encoding the data the operation is performed upon. Nevertheless, we still often transfer the data to a particular place where we execute the operation just to bring the data back to where it came from afterwards. As an example let’s look at the way we usually write our applications for clusters using MPI. This programming model is all about data transfer between nodes. MPI is the prevalent programming model for clusters, and it is fairly straightforward to understand and to use. Therefore, we often write applications in a way that accommodates this model, centered around data transfer. These applications usually work well for smaller problem sizes and for regular data structures. The larger the amount of data we have to churn and the more irregular the problem domain becomes, the worse the overall machine utilization and the (strong) scaling characteristics become. While it is not impossible to implement more dynamic, data driven, and asynchronous applications using MPI, it is somewhat difficult to do so. At the same time, if we look at applications that prefer to execute the code close to the locality where the data was placed, i.e., utilizing active messages (for instance based on Charm++), we see better asynchrony, simpler application codes, and improved scaling.

Favor message driven computation over message passing¶

Today’s prevalently used programming model on parallel (multi-node) systems is MPI. It is based on message passing, as the name implies, which means that the receiver has to be aware of a message about to come in. Both codes, the sender and the receiver, have to synchronize in order to perform the communication step. Even the newer, asynchronous interfaces require explicitly coding the algorithms around the required communication scheme. As a result, everything but the most trivial MPI applications spends a considerable amount of time waiting for incoming messages, thus, causing starvation and latencies to impede full resource utilization. The more complex and more dynamic the data structures and algorithms become, the larger the adverse effects. The community discovered message-driven and data-driven methods of implementing algorithms a long time ago, and systems such as Charm++ have already integrated active messages demonstrating the validity of the concept. Message-driven computation allows for sending messages without requiring the receiver to actively wait for them. Any incoming message is handled asynchronously and triggers the encoded action by passing along arguments and—possibly—continuations. HPX combines this scheme with work-queue based scheduling as described above, which allows the system to almost completely overlap any communication with useful work, thereby minimizing latencies.

Quick start¶

This section is intended to get you to the point of running a basic HPX program as quickly as possible. To that end we skip many details but instead give you hints and links to more details along the way.

We assume that you are on a Unix system with access to reasonably recent

packages. You should have cmake and make available for the build system

(pkg-config is also supported, see Using HPX with pkg-config).

Getting HPX¶

Download a tarball of the latest release from HPX Downloads and

unpack it or clone the repository directly using git:

git clone https://github.com/STEllAR-GROUP/hpx.git

It is also recommended that you check out the latest stable tag:

git checkout 1.7.1

HPX dependencies¶

The minimum dependencies needed to use HPX are Boost and Portable Hardware Locality (HWLOC). If these

are not available through your system package manager, see

Installing Boost and Installing Hwloc for instructions on how

to build them yourself. In addition to Boost and Portable Hardware Locality (HWLOC), it is recommended

that you don’t use the system allocator, but instead use either tcmalloc

from google-perftools (default) or jemalloc for better performance. If you

would like to try HPX without a custom allocator at this point, you can

configure HPX to use the system allocator in the next step.

A full list of required and optional dependencies, including recommended versions, is available at Prerequisites.

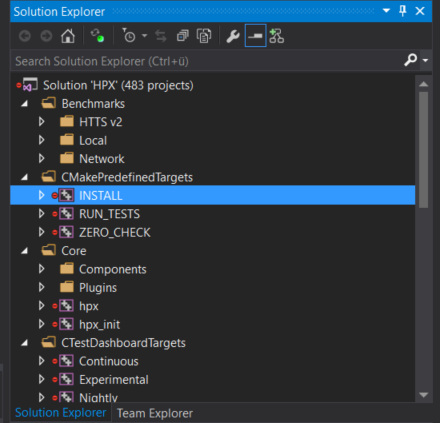

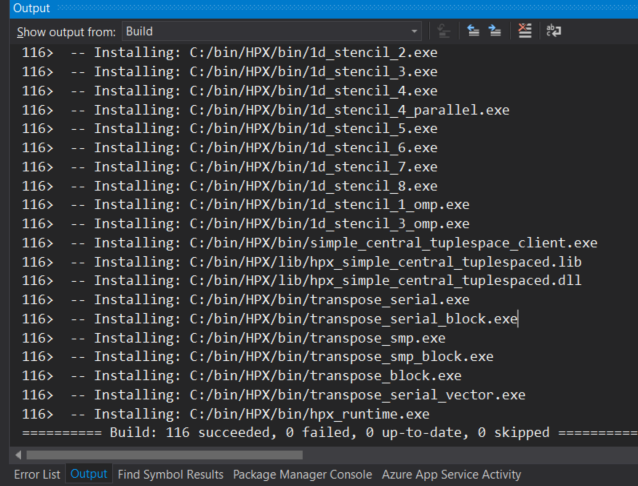

Building HPX¶

Once you have the source code and the dependencies, set up a separate build directory and configure the project. Assuming all your dependencies are in paths known to CMake, the following gets you started:

# In the HPX source directory

mkdir build && cd build

cmake -DCMAKE_INSTALL_PREFIX=/install/path ..

make install

This will build the core HPX libraries and examples, and install them to your

chosen location. If you want to install HPX to system folders, simply leave out

the CMAKE_INSTALL_PREFIX option. This may take a while. To speed up the

process, launch more jobs by passing the -jN option to make.

Tip

Do not set only -j (i.e. -j without an explicit number of jobs)

unless you have a lot of memory available on your machine.

Tip

If you want to change CMake variables for your build, it is usually a good

idea to start with a clean build directory to avoid configuration problems.

It is especially important that you use a clean build directory when changing

between Release and Debug modes.

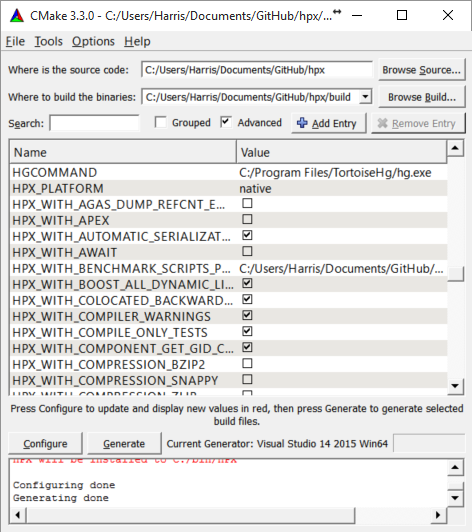

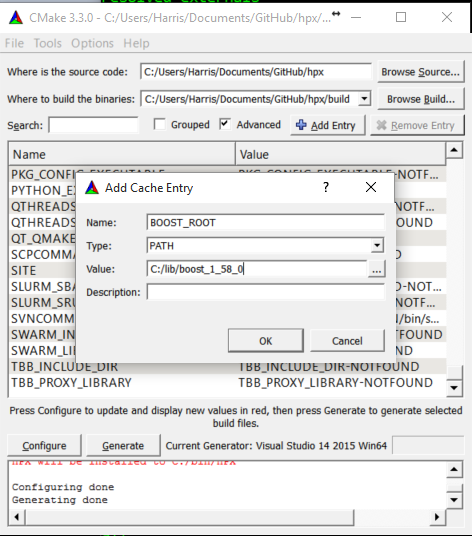

If your dependencies are in custom locations, you may need to tell CMake where to find them by passing one or more of the following options to CMake:

-DBOOST_ROOT=/path/to/boost

-DHWLOC_ROOT=/path/to/hwloc

-DTCMALLOC_ROOT=/path/to/tcmalloc

-DJEMALLOC_ROOT=/path/to/jemalloc

If you want to try HPX without using a custom allocator pass

-DHPX_WITH_MALLOC=system to CMake.

Important

If you are building HPX for a system with more than 64 processing units,

you must change the CMake variables HPX_WITH_MORE_THAN_64_THREADS (to

On) and HPX_WITH_MAX_CPU_COUNT (to a value at least as big as the

number of (virtual) cores on your system).

To build the tests, run make tests. To run the tests, run either make test

or use ctest for more control over which tests to run. You can run single

tests for example with ctest --output-on-failure -R

tests.unit.parallel.algorithms.for_loop or a whole group of tests with ctest

--output-on-failure -R tests.unit.

If you did not run make install earlier, do so now or build the

hello_world_1 example by running:

make hello_world_1

HPX executables end up in the bin directory in your build directory. You

can now run hello_world_1 and should see the following output:

./bin/hello_world_1

Hello World!

You’ve just run an example which prints Hello World! from the HPX runtime.

The source for the example is in examples/quickstart/hello_world_1.cpp. The

hello_world_distributed example (also available in the

examples/quickstart directory) is a distributed hello world program, which is

described in Remote execution with actions: Hello world. It provides a gentle introduction to

the distributed aspects of HPX.

Tip

Most build targets in HPX have two names: a simple name and

a hierarchical name corresponding to what type of example or

test the target is. If you are developing HPX it is often helpful to run

make help to get a list of available targets. For example, make help |

grep hello_world outputs the following:

... examples.quickstart.hello_world_2

... hello_world_2

... examples.quickstart.hello_world_1

... hello_world_1

... examples.quickstart.hello_world_distributed

... hello_world_distributed

It is also possible to build, for instance, all quickstart examples using make

examples.quickstart.

Installing and building HPX via vcpkg¶

You can download and install HPX using the vcpkg <https://github.com/Microsoft/vcpkg> dependency manager:

git clone https://github.com/Microsoft/vcpkg.git

cd vcpkg

./bootstrap-vcpkg.sh

./vcpkg integrate install

vcpkg install hpx

The HPX port in vcpkg is kept up to date by Microsoft team members and community contributors. If the version is out of date, please create an issue or pull request <https://github.com/Microsoft/vcpkg> on the vcpkg repository.

Hello, World!¶

The following CMakeLists.txt is a minimal example of what you need in order to

build an executable using CMake and HPX:

cmake_minimum_required(VERSION 3.17)

project(my_hpx_project CXX)

find_package(HPX REQUIRED)

add_executable(my_hpx_program main.cpp)

target_link_libraries(my_hpx_program HPX::hpx HPX::wrap_main HPX::iostreams_component)

Note

You will most likely have more than one main.cpp file in your project.

See the section on Using HPX with CMake-based projects for more details on how to use

add_hpx_executable.

Note

HPX::wrap_main is required if you are implicitly using main() as the

runtime entry point. See Re-use the main() function as the main HPX entry point for more information.

Note

HPX::iostreams_component is optional for a minimal project but lets us

use the HPX equivalent of std::cout, i.e., the HPX The HPX I/O-streams component

functionality in our application.

Create a new project directory and a CMakeLists.txt with the contents above.

Also create a main.cpp with the contents below.

// Including 'hpx/hpx_main.hpp' instead of the usual 'hpx/hpx_init.hpp' enables

// to use the plain C-main below as the direct main HPX entry point.

#include <hpx/hpx_main.hpp>

#include <hpx/iostream.hpp>

int main()

{

// Say hello to the world!

hpx::cout << "Hello World!\n" << hpx::flush;

return 0;

}

Then, in your project directory run the following:

mkdir build && cd build

cmake -DCMAKE_PREFIX_PATH=/path/to/hpx/installation ..

make all

./my_hpx_program

The program looks almost like a regular C++ hello world with the exception of

the two includes and hpx::cout. When you include hpx_main.hpp some

things will be done behind the scenes to make sure that main actually gets

launched on the HPX runtime. So while it looks almost the same you can now use

futures, async, parallel algorithms and more which make use of the HPX

runtime with lightweight threads. hpx::cout is a replacement for

std::cout to make sure printing never blocks a lightweight thread. You can

read more about hpx::cout in The HPX I/O-streams component. If you rebuild and run your

program now, you should see the familiar Hello World!:

./my_hpx_program

Hello World!

Note

You do not have to let HPX take over your main function like in the

example. You can instead keep your normal main function, and define a

separate hpx_main function which acts as the entry point to the HPX

runtime. In that case you start the HPX runtime explicitly by calling

hpx::init:

// Copyright (c) 2007-2012 Hartmut Kaiser

//

// SPDX-License-Identifier: BSL-1.0

// Distributed under the Boost Software License, Version 1.0. (See accompanying

// file LICENSE_1_0.txt or copy at http://www.boost.org/LICENSE_1_0.txt)

///////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////

// The purpose of this example is to initialize the HPX runtime explicitly and

// execute a HPX-thread printing "Hello World!" once. That's all.

//[hello_world_2_getting_started

#include <hpx/hpx_init.hpp>

#include <hpx/iostream.hpp>

int hpx_main(int, char**)

{

// Say hello to the world!

hpx::cout << "Hello World!\n" << hpx::flush;

return hpx::finalize();

}

int main(int argc, char* argv[])

{

return hpx::init(argc, argv);

}

//]

You can also use hpx::start and hpx::stop for a

non-blocking alternative, or use hpx::resume and

hpx::suspend if you need to combine HPX with other runtimes.

See Starting the HPX runtime for more details on how to initialize and run the HPX runtime.

Caution

When including hpx_main.hpp the user-defined main gets renamed and

the real main function is defined by HPX. This means that the

user-defined main must include a return statement, unlike the real

main. If you do not include the return statement, you may end up with

confusing compile time errors mentioning user_main or even runtime

errors.

Writing task-based applications¶

So far we haven’t done anything that can’t be done using the C++ standard library. In this section we will give a short overview of what you can do with HPX on a single node. The essence is to avoid global synchronization and break up your application into small, composable tasks whose dependencies control the flow of your application. Remember, however, that HPX allows you to write distributed applications similarly to how you would write applications for a single node (see Why HPX? and Writing distributed HPX applications).

If you are already familiar with async and futures from the C++ standard

library, the same functionality is available in HPX.

The following terminology is essential when talking about task-based C++ programs:

lightweight thread: Essential for good performance with task-based programs. Lightweight refers to smaller stacks and faster context switching compared to OS threads. Smaller overheads allow the program to be broken up into smaller tasks, which in turns helps the runtime fully utilize all processing units.

async: The most basic way of launching tasks asynchronously. Returns afuture<T>.future<T>: Represents a value of typeTthat will be ready in the future. The value can be retrieved withget(blocking) and one can check if the value is ready withis_ready(non-blocking).shared_future<T>: Same asfuture<T>but can be copied (similar tostd::unique_ptrvsstd::shared_ptr).continuation: A function that is to be run after a previous task has run (represented by a future).

thenis a method offuture<T>that takes a function to run next. Used to build up dataflow DAGs (directed acyclic graphs).shared_futures help you split up nodes in the DAG and functions likewhen_allhelp you join nodes in the DAG.

The following example is a collection of the most commonly used functionality in HPX:

#include <hpx/hpx_main.hpp>

#include <hpx/include/lcos.hpp>

#include <hpx/include/parallel_generate.hpp>

#include <hpx/include/parallel_sort.hpp>

#include <hpx/iostream.hpp>

#include <random>

#include <vector>

void final_task(

hpx::future<hpx::tuple<hpx::future<double>, hpx::future<void>>>)

{

hpx::cout << "in final_task" << hpx::endl;

}

// Avoid ABI incompatibilities between C++11/C++17 as std::rand has exception

// specification in libstdc++.

int rand_wrapper()

{

return std::rand();

}

int main(int, char**)

{

// A function can be launched asynchronously. The program will not block

// here until the result is available.

hpx::future<int> f = hpx::async([]() { return 42; });

hpx::cout << "Just launched a task!" << hpx::endl;

// Use get to retrieve the value from the future. This will block this task

// until the future is ready, but the HPX runtime will schedule other tasks

// if there are tasks available.

hpx::cout << "f contains " << f.get() << hpx::endl;

// Let's launch another task.

hpx::future<double> g = hpx::async([]() { return 3.14; });

// Tasks can be chained using the then method. The continuation takes the

// future as an argument.

hpx::future<double> result = g.then([](hpx::future<double>&& gg) {

// This function will be called once g is ready. gg is g moved

// into the continuation.

return gg.get() * 42.0 * 42.0;

});

// You can check if a future is ready with the is_ready method.

hpx::cout << "Result is ready? " << result.is_ready() << hpx::endl;

// You can launch other work in the meantime. Let's sort a vector.

std::vector<int> v(1000000);

// We fill the vector synchronously and sequentially.

hpx::generate(hpx::execution::seq, std::begin(v), std::end(v),

&rand_wrapper);

// We can launch the sort in parallel and asynchronously.

hpx::future<void> done_sorting = hpx::parallel::sort(

hpx::execution::par( // In parallel.

hpx::execution::task), // Asynchronously.

std::begin(v), std::end(v));

// We launch the final task when the vector has been sorted and result is

// ready using when_all.

auto all = hpx::when_all(result, done_sorting).then(&final_task);

// We can wait for all to be ready.

all.wait();

// all must be ready at this point because we waited for it to be ready.

hpx::cout << (all.is_ready() ? "all is ready!" : "all is not ready...")

<< hpx::endl;

return hpx::finalize();

}

Try copying the contents to your main.cpp file and look at the output. It can

be a good idea to go through the program step by step with a debugger. You can

also try changing the types or adding new arguments to functions to make sure

you can get the types to match. The type of the then method can be especially

tricky to get right (the continuation needs to take the future as an argument).

Note

HPX programs accept command line arguments. The most important one is

--hpx:threads=N to set the number of OS threads used by

HPX. HPX uses one thread per core by default. Play around with the

example above and see what difference the number of threads makes on the

sort function. See Launching and configuring HPX applications for more details on

how and what options you can pass to HPX.

Tip

The example above used the construction hpx::when_all(...).then(...). For

convenience and performance it is a good idea to replace uses of

hpx::when_all(...).then(...) with dataflow. See

Dataflow: Interest calculator for more details on dataflow.

Tip

If possible, try to use the provided parallel algorithms instead of writing your own implementation. This can save you time and the resulting program is often faster.

Next steps¶

If you haven’t done so already, reading the Terminology section will help you get familiar with the terms used in HPX.

The Examples section contains small, self-contained walkthroughs of example HPX programs. The Local to remote: 1D stencil example is a thorough, realistic example starting from a single node implementation and going stepwise to a distributed implementation.

The Manual contains detailed information on writing, building and running HPX applications.

Terminology¶

This section gives definitions for some of the terms used throughout the HPX documentation and source code.

- Locality¶

A locality in HPX describes a synchronous domain of execution, or the domain of bounded upper response time. This normally is just a single node in a cluster or a NUMA domain in a SMP machine.

- Active Global Address Space¶

- AGAS¶

HPX incorporates a global address space. Any executing thread can access any object within the domain of the parallel application with the caveat that it must have appropriate access privileges. The model does not assume that global addresses are cache coherent; all loads and stores will deal directly with the site of the target object. All global addresses within a Synchronous Domain are assumed to be cache coherent for those processor cores that incorporate transparent caches. The Active Global Address Space used by HPX differs from research PGAS models. Partitioned Global Address Space is passive in their means of address translation. Copy semantics, distributed compound operations, and affinity relationships are some of the global functionality supported by AGAS.

- Process¶

The concept of the “process” in HPX is extended beyond that of either sequential execution or communicating sequential processes. While the notion of process suggests action (as do “function” or “subroutine”) it has a further responsibility of context, that is, the logical container of program state. It is this aspect of operation that process is employed in HPX. Furthermore, referring to “parallel processes” in HPX designates the presence of parallelism within the context of a given process, as well as the coarse grained parallelism achieved through concurrency of multiple processes of an executing user job. HPX processes provide a hierarchical name space within the framework of the active global address space and support multiple means of internal state access from external sources.

- Parcel¶

The Parcel is a component in HPX that communicates data, invokes an action at a distance, and distributes flow-control through the migration of continuations. Parcels bridge the gap of asynchrony between synchronous domains while maintaining symmetry of semantics between local and global execution. Parcels enable message-driven computation and may be seen as a form of “active messages”. Other important forms of message-driven computation predating active messages include dataflow tokens, the J-machine’s support for remote method instantiation, and at the coarse grained variations of Unix remote procedure calls, among others. This enables work to be moved to the data as well as performing the more common action of bringing data to the work. A parcel can cause actions to occur remotely and asynchronously, among which are the creation of threads at different system nodes or synchronous domains.

- Local Control Object¶

- Lightweight Control Object¶

- LCO¶

A local control object (sometimes called a lightweight control object) is a general term for the synchronization mechanisms used in HPX. Any object implementing a certain concept can be seen as an LCO. This concepts encapsulates the ability to be triggered by one or more events which when taking the object into a predefined state will cause a thread to be executed. This could either create a new thread or resume an existing thread.

The LCO is a family of synchronization functions potentially representing many classes of synchronization constructs, each with many possible variations and multiple instances. The LCO is sufficiently general that it can subsume the functionality of conventional synchronization primitives such as spinlocks, mutexes, semaphores, and global barriers. However due to the rich concept an LCO can represent powerful synchronization and control functionality not widely employed, such as dataflow and futures (among others), which open up enormous opportunities for rich diversity of distributed control and operation.

See Using LCOs for more details on how to use LCOs in HPX.

- Action¶

An action is a function that can be invoked remotely. In HPX a plain function can be made into an action using a macro. See Applying actions for details on how to use actions in HPX.

- Component¶

A component is a C++ object which can be accessed remotely. A component can also contain member functions which can be invoked remotely. These are referred to as component actions. See Writing components for details on how to use components in HPX.

Examples¶

The following sections analyze some examples to help you get familiar with the HPX style of programming. We start off with simple examples that utilize basic HPX elements and then begin to expose the reader to the more complex and powerful HPX concepts.

Asynchronous execution with hpx::async: Fibonacci¶

The Fibonacci sequence is a sequence of numbers starting with 0 and 1 where every subsequent number is the sum of the previous two numbers. In this example, we will use HPX to calculate the value of the n-th element of the Fibonacci sequence. In order to compute this problem in parallel, we will use a facility known as a future.

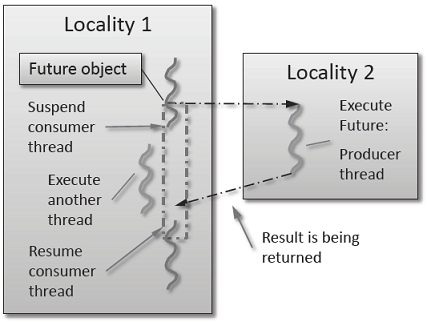

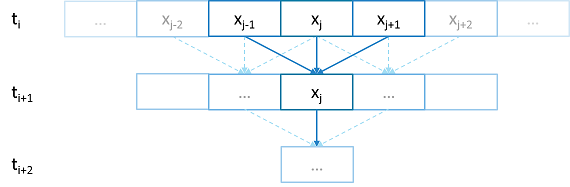

As shown in the Fig. 1 below, a future encapsulates a delayed computation. It acts as a proxy for a result initially not known, most of the time because the computation of the result has not completed yet. The future synchronizes the access of this value by optionally suspending any HPX-threads requesting the result until the value is available. When a future is created, it spawns a new HPX-thread (either remotely with a parcel or locally by placing it into the thread queue) which, when run, will execute the function associated with the future. The arguments of the function are bound when the future is created.

Fig. 1 Schematic of a future execution.¶

Once the function has finished executing, a write operation is performed on the future. The write operation marks the future as completed, and optionally stores data returned by the function. When the result of the delayed computation is needed, a read operation is performed on the future. If the future’s function hasn’t completed when a read operation is performed on it, the reader HPX-thread is suspended until the future is ready. The future facility allows HPX to schedule work early in a program so that when the function value is needed it will already be calculated and available. We use this property in our Fibonacci example below to enable its parallel execution.

Setup¶

The source code for this example can be found here:

fibonacci_local.cpp.

To compile this program, go to your HPX build directory (see HPX build system for information on configuring and building HPX) and enter:

make examples.quickstart.fibonacci_local

To run the program type:

./bin/fibonacci_local

This should print (time should be approximate):

fibonacci(10) == 55

elapsed time: 0.002430 [s]

This run used the default settings, which calculate the tenth element of the

Fibonacci sequence. To declare which Fibonacci value you want to calculate, use

the --n-value option. Additionally you can use the --hpx:threads

option to declare how many OS-threads you wish to use when running the program.

For instance, running:

./bin/fibonacci --n-value 20 --hpx:threads 4

Will yield:

fibonacci(20) == 6765

elapsed time: 0.062854 [s]

Walkthrough¶

Now that you have compiled and run the code, let’s look at how the code works.

Since this code is written in C++, we will begin with the main() function.

Here you can see that in HPX, main() is only used to initialize the

runtime system. It is important to note that application-specific command line

options are defined here. HPX uses Boost.Program Options for command line

processing. You can see that our programs --n-value option is set by calling

the add_options() method on an instance of

hpx::program_options::options_description. The default value of the

variable is set to 10. This is why when we ran the program for the first time

without using the --n-value option the program returned the 10th value of

the Fibonacci sequence. The constructor argument of the description is the text

that appears when a user uses the --hpx:help option to see what

command line options are available. HPX_APPLICATION_STRING is a macro that

expands to a string constant containing the name of the HPX application

currently being compiled.

In HPX main() is used to initialize the runtime system and pass the

command line arguments to the program. If you wish to add command line options

to your program you would add them here using the instance of the Boost class

options_description, and invoking the public member function

.add_options() (see Boost Documentation for more details). hpx::init

calls hpx_main() after setting up HPX, which is where the logic of our

program is encoded.

int main(int argc, char* argv[])

{

// Configure application-specific options

hpx::program_options::options_description desc_commandline(

"Usage: " HPX_APPLICATION_STRING " [options]");

desc_commandline.add_options()("n-value",

hpx::program_options::value<std::uint64_t>()->default_value(10),

"n value for the Fibonacci function");

// Initialize and run HPX

hpx::init_params init_args;

init_args.desc_cmdline = desc_commandline;

return hpx::init(argc, argv, init_args);

}

The hpx::init function in main() starts the runtime system, and

invokes hpx_main() as the first HPX-thread. Below we can see that the

basic program is simple. The command line option --n-value is read in, a

timer (hpx::chrono::high_resolution_timer) is set up to record the

time it takes to do the computation, the fibonacci function is invoked

synchronously, and the answer is printed out.

int hpx_main(hpx::program_options::variables_map& vm)

{

// extract command line argument, i.e. fib(N)

std::uint64_t n = vm["n-value"].as<std::uint64_t>();

{

// Keep track of the time required to execute.

hpx::chrono::high_resolution_timer t;

std::uint64_t r = fibonacci(n);

char const* fmt = "fibonacci({1}) == {2}\nelapsed time: {3} [s]\n";

hpx::util::format_to(std::cout, fmt, n, r, t.elapsed());

}

return hpx::finalize(); // Handles HPX shutdown

}

The fibonacci function itself is synchronous as the work done inside is

asynchronous. To understand what is happening we have to look inside the

fibonacci function:

std::uint64_t fibonacci(std::uint64_t n)

{

if (n < 2)

return n;

// Invoking the Fibonacci algorithm twice is inefficient.

// However, we intentionally demonstrate it this way to create some

// heavy workload.

hpx::future<std::uint64_t> n1 = hpx::async(fibonacci, n - 1);

hpx::future<std::uint64_t> n2 = hpx::async(fibonacci, n - 2);

return n1.get() +

n2.get(); // wait for the Futures to return their values

}

This block of code looks similar to regular C++ code. First, if (n < 2),

meaning n is 0 or 1, then we return 0 or 1 (recall the first element of the

Fibonacci sequence is 0 and the second is 1). If n is larger than 1 we spawn two

new tasks whose results are contained in n1 and n2. This is done using

hpx::async which takes as arguments a function (function pointer,

object or lambda) and the arguments to the function. Instead of returning a

std::uint64_t like fibonacci does, hpx::async returns a future of a

std::uint64_t, i.e. hpx::future<std::uint64_t>. Each of these futures

represents an asynchronous, recursive call to fibonacci. After we’ve created

the futures, we wait for both of them to finish computing, we add them together,

and return that value as our result. We get the values from the futures using

the get method. The recursive call tree will continue until n is equal to 0

or 1, at which point the value can be returned because it is implicitly known.

When this termination condition is reached, the futures can then be added up,

producing the n-th value of the Fibonacci sequence.

Note that calling get potentially blocks the calling HPX-thread, and lets

other HPX-threads run in the meantime. There are, however, more efficient ways

of doing this. examples/quickstart/fibonacci_futures.cpp contains many more

variations of locally computing the Fibonacci numbers, where each method makes

different tradeoffs in where asynchrony and parallelism is applied. To get

started, however, the method above is sufficient and optimizations can be

applied once you are more familiar with HPX. The example

Dataflow: Interest calculator presents dataflow, which is a way to more

efficiently chain together multiple tasks.

Asynchronous execution with hpx::async and actions: Fibonacci¶

This example extends the previous example by

introducing actions: functions that can be run remotely. In this

example, however, we will still only run the action locally. The mechanism to

execute actions stays the same: hpx::async. Later

examples will demonstrate running actions on remote localities

(e.g. Remote execution with actions: Hello world).

Setup¶

The source code for this example can be found here:

fibonacci.cpp.

To compile this program, go to your HPX build directory (see HPX build system for information on configuring and building HPX) and enter:

make examples.quickstart.fibonacci

To run the program type:

./bin/fibonacci

This should print (time should be approximate):

fibonacci(10) == 55

elapsed time: 0.00186288 [s]

This run used the default settings, which calculate the tenth element of the

Fibonacci sequence. To declare which Fibonacci value you want to calculate, use

the --n-value option. Additionally you can use the --hpx:threads

option to declare how many OS-threads you wish to use when running the program.

For instance, running:

./bin/fibonacci --n-value 20 --hpx:threads 4

Will yield:

fibonacci(20) == 6765

elapsed time: 0.233827 [s]

Walkthrough¶

The code needed to initialize the HPX runtime is the same as in the previous example:

int main(int argc, char* argv[])

{

// Configure application-specific options

hpx::program_options::options_description

desc_commandline("Usage: " HPX_APPLICATION_STRING " [options]");

desc_commandline.add_options()

( "n-value",

hpx::program_options::value<std::uint64_t>()->default_value(10),

"n value for the Fibonacci function")

;

// Initialize and run HPX

hpx::init_params init_args;

init_args.desc_cmdline = desc_commandline;

return hpx::init(argc, argv, init_args);

}

The hpx::init function in main() starts the runtime system, and

invokes hpx_main() as the first HPX-thread. The command line option

--n-value is read in, a timer

(hpx::chrono::high_resolution_timer) is set up to record the time it

takes to do the computation, the fibonacci action is invoked

synchronously, and the answer is printed out.

int hpx_main(hpx::program_options::variables_map& vm)

{

// extract command line argument, i.e. fib(N)

std::uint64_t n = vm["n-value"].as<std::uint64_t>();

{

// Keep track of the time required to execute.

hpx::chrono::high_resolution_timer t;

// Wait for fib() to return the value

fibonacci_action fib;

std::uint64_t r = fib(hpx::find_here(), n);

char const* fmt = "fibonacci({1}) == {2}\nelapsed time: {3} [s]\n";

hpx::util::format_to(std::cout, fmt, n, r, t.elapsed());

}

return hpx::finalize(); // Handles HPX shutdown

}

Upon a closer look we see that we’ve created a std::uint64_t to store the

result of invoking our fibonacci_action fib. This action will

launch synchronously (as the work done inside of the action will be

asynchronous itself) and return the result of the Fibonacci sequence. But wait,

what is an action? And what is this fibonacci_action? For starters,

an action is a wrapper for a function. By wrapping functions, HPX can

send packets of work to different processing units. These vehicles allow users

to calculate work now, later, or on certain nodes. The first argument to our

action is the location where the action should be run. In this

case, we just want to run the action on the machine that we are

currently on, so we use hpx::find_here. To

further understand this we turn to the code to find where fibonacci_action

was defined:

// forward declaration of the Fibonacci function

std::uint64_t fibonacci(std::uint64_t n);

// This is to generate the required boilerplate we need for the remote

// invocation to work.

HPX_PLAIN_ACTION(fibonacci, fibonacci_action);

A plain action is the most basic form of action. Plain

actions wrap simple global functions which are not associated with any

particular object (we will discuss other types of actions in

Components and actions: Accumulator). In this block of code the function fibonacci()

is declared. After the declaration, the function is wrapped in an action

in the declaration HPX_PLAIN_ACTION. This function takes two

arguments: the name of the function that is to be wrapped and the name of the

action that you are creating.

This picture should now start making sense. The function fibonacci() is

wrapped in an action fibonacci_action, which was run synchronously

but created asynchronous work, then returns a std::uint64_t representing the

result of the function fibonacci(). Now, let’s look at the function

fibonacci():

std::uint64_t fibonacci(std::uint64_t n)

{

if (n < 2)

return n;

// We restrict ourselves to execute the Fibonacci function locally.

hpx::naming::id_type const locality_id = hpx::find_here();

// Invoking the Fibonacci algorithm twice is inefficient.

// However, we intentionally demonstrate it this way to create some

// heavy workload.

fibonacci_action fib;

hpx::future<std::uint64_t> n1 =

hpx::async(fib, locality_id, n - 1);

hpx::future<std::uint64_t> n2 =

hpx::async(fib, locality_id, n - 2);

return n1.get() + n2.get(); // wait for the Futures to return their values

}

This block of code is much more straightforward and should look familiar from

the previous example. First, if (n < 2),

meaning n is 0 or 1, then we return 0 or 1 (recall the first element of the

Fibonacci sequence is 0 and the second is 1). If n is larger than 1 we spawn two

tasks using hpx::async. Each of these futures represents an

asynchronous, recursive call to fibonacci. As previously we wait for both

futures to finish computing, get the results, add them together, and return that

value as our result. The recursive call tree will continue until n is equal to 0

or 1, at which point the value can be returned because it is implicitly known.

When this termination condition is reached, the futures can then be added up,

producing the n-th value of the Fibonacci sequence.

Remote execution with actions: Hello world¶

This program will print out a hello world message on every OS-thread on every locality. The output will look something like this:

hello world from OS-thread 1 on locality 0

hello world from OS-thread 1 on locality 1

hello world from OS-thread 0 on locality 0

hello world from OS-thread 0 on locality 1

Setup¶

The source code for this example can be found here:

hello_world_distributed.cpp.

To compile this program, go to your HPX build directory (see HPX build system for information on configuring and building HPX) and enter:

make examples.quickstart.hello_world_distributed

To run the program type:

./bin/hello_world_distributed

This should print:

hello world from OS-thread 0 on locality 0

To use more OS-threads use the command line option --hpx:threads and

type the number of threads that you wish to use. For example, typing:

./bin/hello_world_distributed --hpx:threads 2

will yield:

hello world from OS-thread 1 on locality 0

hello world from OS-thread 0 on locality 0

Notice how the ordering of the two print statements will change with subsequent runs. To run this program on multiple localities please see the section How to use HPX applications with PBS.

Walkthrough¶

Now that you have compiled and run the code, let’s look at how the code works,

beginning with main():

// Here is the main entry point. By using the include 'hpx/hpx_main.hpp' HPX

// will invoke the plain old C-main() as its first HPX thread.

int main()

{

// Get a list of all available localities.

std::vector<hpx::naming::id_type> localities = hpx::find_all_localities();

// Reserve storage space for futures, one for each locality.

std::vector<hpx::lcos::future<void>> futures;

futures.reserve(localities.size());

for (hpx::naming::id_type const& node : localities)

{

// Asynchronously start a new task. The task is encapsulated in a

// future, which we can query to determine if the task has

// completed.

typedef hello_world_foreman_action action_type;

futures.push_back(hpx::async<action_type>(node));

}

// The non-callback version of hpx::lcos::wait_all takes a single parameter,

// a vector of futures to wait on. hpx::wait_all only returns when

// all of the futures have finished.

hpx::wait_all(futures);

return 0;

}

In this excerpt of the code we again see the use of futures. This time the

futures are stored in a vector so that they can easily be accessed.

hpx::wait_all is a family of functions that wait on for an

std::vector<> of futures to become ready. In this piece of code, we are

using the synchronous version of hpx::wait_all, which takes one

argument (the std::vector<> of futures to wait on). This function will not

return until all the futures in the vector have been executed.

In Asynchronous execution with hpx::async and actions: Fibonacci we used hpx::find_here to specify the

target of our actions. Here, we instead use

hpx::find_all_localities, which returns an std::vector<>

containing the identifiers of all the machines in the system, including the one

that we are on.

As in Asynchronous execution with hpx::async and actions: Fibonacci our futures are set using

hpx::async<>. The hello_world_foreman_action is declared

here:

// Define the boilerplate code necessary for the function 'hello_world_foreman'

// to be invoked as an HPX action.

HPX_PLAIN_ACTION(hello_world_foreman, hello_world_foreman_action);

Another way of thinking about this wrapping technique is as follows: functions (the work to be done) are wrapped in actions, and actions can be executed locally or remotely (e.g. on another machine participating in the computation).

Now it is time to look at the hello_world_foreman() function which was

wrapped in the action above:

void hello_world_foreman()

{

// Get the number of worker OS-threads in use by this locality.

std::size_t const os_threads = hpx::get_os_thread_count();

// Populate a set with the OS-thread numbers of all OS-threads on this

// locality. When the hello world message has been printed on a particular

// OS-thread, we will remove it from the set.

std::set<std::size_t> attendance;

for (std::size_t os_thread = 0; os_thread < os_threads; ++os_thread)

attendance.insert(os_thread);

// As long as there are still elements in the set, we must keep scheduling

// HPX-threads. Because HPX features work-stealing task schedulers, we have

// no way of enforcing which worker OS-thread will actually execute

// each HPX-thread.

while (!attendance.empty())

{

// Each iteration, we create a task for each element in the set of

// OS-threads that have not said "Hello world". Each of these tasks

// is encapsulated in a future.

std::vector<hpx::lcos::future<std::size_t>> futures;

futures.reserve(attendance.size());

for (std::size_t worker : attendance)

{

// Asynchronously start a new task. The task is encapsulated in a

// future, which we can query to determine if the task has

// completed. We give the task a hint to run on a particular worker

// thread, but no guarantees are given by the scheduler that the

// task will actually run on that worker thread.

hpx::execution::parallel_executor exec(

hpx::threads::thread_schedule_hint(

hpx::threads::thread_schedule_hint_mode::thread,

static_cast<std::int16_t>(worker)));

futures.push_back(hpx::async(exec, hello_world_worker, worker));

}

// Wait for all of the futures to finish. The callback version of the

// hpx::lcos::wait_each function takes two arguments: a vector of futures,

// and a binary callback. The callback takes two arguments; the first

// is the index of the future in the vector, and the second is the

// return value of the future. hpx::lcos::wait_each doesn't return until

// all the futures in the vector have returned.

hpx::lcos::local::spinlock mtx;

hpx::lcos::wait_each(hpx::unwrapping([&](std::size_t t) {

if (std::size_t(-1) != t)

{

std::lock_guard<hpx::lcos::local::spinlock> lk(mtx);

attendance.erase(t);

}

}),

futures);

}

}

Now, before we discuss hello_world_foreman(), let’s talk about the

hpx::wait_each function.

The version of hpx::lcos::wait_each invokes a callback function

provided by the user, supplying the callback function with the result of the

future.

In hello_world_foreman(), an std::set<> called attendance keeps

track of which OS-threads have printed out the hello world message. When the

OS-thread prints out the statement, the future is marked as ready, and

hpx::lcos::wait_each in hello_world_foreman(). If it is not

executing on the correct OS-thread, it returns a value of -1, which causes

hello_world_foreman() to leave the OS-thread id in attendance.

std::size_t hello_world_worker(std::size_t desired)

{

// Returns the OS-thread number of the worker that is running this

// HPX-thread.

std::size_t current = hpx::get_worker_thread_num();

if (current == desired)

{

// The HPX-thread has been run on the desired OS-thread.

char const* msg = "hello world from OS-thread {1} on locality {2}\n";

hpx::util::format_to(hpx::cout, msg, desired, hpx::get_locality_id())

<< std::flush;

return desired;

}

// This HPX-thread has been run by the wrong OS-thread, make the foreman

// try again by rescheduling it.

return std::size_t(-1);

}

Because HPX features work stealing task schedulers, there is no way to guarantee that an action will be scheduled on a particular OS-thread. This is why we must use a guess-and-check approach.

Components and actions: Accumulator¶

The accumulator example demonstrates the use of components. Components are C++ classes that expose methods as a type of HPX action. These actions are called component actions.

Components are globally named, meaning that a component action can be called remotely (e.g., from another machine). There are two accumulator examples in HPX.

In the Asynchronous execution with hpx::async and actions: Fibonacci and the Remote execution with actions: Hello world, we introduced plain actions, which wrapped global functions. The target of a plain action is an identifier which refers to a particular machine involved in the computation. For plain actions, the target is the machine where the action will be executed.

Component actions, however, do not target machines. Instead, they target component instances. The instance may live on the machine that we’ve invoked the component action from, or it may live on another machine.

The component in this example exposes three different functions:

reset()- Resets the accumulator value to 0.add(arg)- Addsargto the accumulators value.query()- Queries the value of the accumulator.

This example creates an instance of the accumulator, and then allows the user to enter commands at a prompt, which subsequently invoke actions on the accumulator instance.

Setup¶

The source code for this example can be found here:

accumulator_client.cpp.

To compile this program, go to your HPX build directory (see HPX build system for information on configuring and building HPX) and enter:

make examples.accumulators.accumulator

To run the program type:

./bin/accumulator_client

Once the program starts running, it will print the following prompt and then wait for input. An example session is given below:

commands: reset, add [amount], query, help, quit

> add 5

> add 10

> query

15

> add 2

> query

17

> reset

> add 1

> query

1

> quit

Walkthrough¶

Now, let’s take a look at the source code of the accumulator example. This

example consists of two parts: an HPX component library (a library that

exposes an HPX component) and a client application which uses the library.

This walkthrough will cover the HPX component library. The code for the client

application can be found here: accumulator_client.cpp.

An HPX component is represented by two C++ classes:

A server class - The implementation of the component’s functionality.

A client class - A high-level interface that acts as a proxy for an instance of the component.

Typically, these two classes both have the same name, but the server class

usually lives in different sub-namespaces (server). For example, the full

names of the two classes in accumulator are:

examples::server::accumulator(server class)examples::accumulator(client class)

The server class¶

The following code is from: accumulator.hpp.

All HPX component server classes must inherit publicly from the HPX

component base class: hpx::components::component_base

The accumulator component inherits from

hpx::components::locking_hook. This allows the runtime system to

ensure that all action invocations are serialized. That means that the system

ensures that no two actions are invoked at the same time on a given component

instance. This makes the component thread safe and no additional locking has to

be implemented by the user. Moreover, an accumulator component is a component

because it also inherits from hpx::components::component_base (the

template argument passed to locking_hook is used as its base class). The

following snippet shows the corresponding code:

class accumulator

: public hpx::components::locking_hook<

hpx::components::component_base<accumulator> >

Our accumulator class will need a data member to store its value in, so let’s declare a data member:

argument_type value_;

The constructor for this class simply initializes value_ to 0:

accumulator() : value_(0) {}

Next, let’s look at the three methods of this component that we will be exposing as component actions:

Here are the action types. These types wrap the methods we’re exposing. The wrapping technique is very similar to the one used in the Asynchronous execution with hpx::async and actions: Fibonacci and the Remote execution with actions: Hello world:

HPX_DEFINE_COMPONENT_ACTION(accumulator, reset);

HPX_DEFINE_COMPONENT_ACTION(accumulator, add);

HPX_DEFINE_COMPONENT_ACTION(accumulator, query);

The last piece of code in the server class header is the declaration of the action type registration code:

HPX_REGISTER_ACTION_DECLARATION(

examples::server::accumulator::reset_action,

accumulator_reset_action);

HPX_REGISTER_ACTION_DECLARATION(

examples::server::accumulator::add_action,

accumulator_add_action);

HPX_REGISTER_ACTION_DECLARATION(

examples::server::accumulator::query_action,

accumulator_query_action);

Note

The code above must be placed in the global namespace.

The rest of the registration code is in

accumulator.cpp

///////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////

// Add factory registration functionality.

HPX_REGISTER_COMPONENT_MODULE();

///////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////

typedef hpx::components::component<

examples::server::accumulator

> accumulator_type;

HPX_REGISTER_COMPONENT(accumulator_type, accumulator);

///////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////

// Serialization support for accumulator actions.

HPX_REGISTER_ACTION(

accumulator_type::wrapped_type::reset_action,

accumulator_reset_action);

HPX_REGISTER_ACTION(

accumulator_type::wrapped_type::add_action,

accumulator_add_action);

HPX_REGISTER_ACTION(

accumulator_type::wrapped_type::query_action,

accumulator_query_action);

Note

The code above must be placed in the global namespace.

The client class¶

The following code is from accumulator.hpp.

The client class is the primary interface to a component instance. Client classes are used to create components:

// Create a component on this locality.

examples::accumulator c = hpx::new_<examples::accumulator>(hpx::find_here());

and to invoke component actions:

c.add(hpx::launch::apply, 4);

Clients, like servers, need to inherit from a base class, this time,

hpx::components::client_base:

class accumulator

: public hpx::components::client_base<

accumulator, server::accumulator

>

For readability, we typedef the base class like so:

typedef hpx::components::client_base<

accumulator, server::accumulator

> base_type;

Here are examples of how to expose actions through a client class:

There are a few different ways of invoking actions:

Non-blocking: For actions that don’t have return types, or when we do not care about the result of an action, we can invoke the action using fire-and-forget semantics. This means that once we have asked HPX to compute the action, we forget about it completely and continue with our computation. We use

hpx::applyto invoke an action in a non-blocking fashion.

void reset(hpx::launch::apply_policy)

{

HPX_ASSERT(this->get_id());

typedef server::accumulator::reset_action action_type;

hpx::apply<action_type>(this->get_id());

}

Asynchronous: Futures, as demonstrated in Asynchronous execution with hpx::async: Fibonacci, Asynchronous execution with hpx::async and actions: Fibonacci, and the Remote execution with actions: Hello world, enable asynchronous action invocation. Here’s an example from the accumulator client class:

hpx::future<argument_type> query(hpx::launch::async_policy)

{

HPX_ASSERT(this->get_id());

typedef server::accumulator::query_action action_type;

return hpx::async<action_type>(hpx::launch::async, this->get_id());

}

Synchronous: To invoke an action in a fully synchronous manner, we can simply call

hpx::async().get()(i.e., create a future and immediately wait on it to be ready). Here’s an example from the accumulator client class:

void add(argument_type arg)

{

HPX_ASSERT(this->get_id());

typedef server::accumulator::add_action action_type;

action_type()(this->get_id(), arg);

}

Note that this->get_id() references a data member of the

hpx::components::client_base base class which identifies the server

accumulator instance.

hpx::naming::id_type is a type which represents a global identifier

in HPX. This type specifies the target of an action. This is the type that is

returned by hpx::find_here in which case it represents the

locality the code is running on.

Dataflow: Interest calculator¶

HPX provides its users with several different tools to simply express parallel concepts. One of these tools is a local control object (LCO) called dataflow. An LCO is a type of component that can spawn a new thread when triggered. They are also distinguished from other components by a standard interface that allow users to understand and use them easily. A Dataflow, being an LCO, is triggered when the values it depends on become available. For instance, if you have a calculation X that depends on the results of three other calculations, you could set up a dataflow that would begin the calculation X as soon as the other three calculations have returned their values. Dataflows are set up to depend on other dataflows. It is this property that makes dataflow a powerful parallelization tool. If you understand the dependencies of your calculation, you can devise a simple algorithm that sets up a dependency tree to be executed. In this example, we calculate compound interest. To calculate compound interest, one must calculate the interest made in each compound period, and then add that interest back to the principal before calculating the interest made in the next period. A practical person would, of course, use the formula for compound interest:

where \(F\) is the future value, \(P\) is the principal value, \(i\) is the interest rate, and \(n\) is the number of compound periods.

However, for the sake of this example, we have chosen to manually calculate the future value by iterating:

and

Setup¶

The source code for this example can be found here:

interest_calculator.cpp.

To compile this program, go to your HPX build directory (see HPX build system for information on configuring and building HPX) and enter:

make examples.quickstart.interest_calculator

To run the program type:

./bin/interest_calculator --principal 100 --rate 5 --cp 6 --time 36

This should print:

Final amount: 134.01

Amount made: 34.0096

Walkthrough¶

Let us begin with main. Here we can see that we again are using

Boost.Program Options to set our command line variables (see

Asynchronous execution with hpx::async and actions: Fibonacci for more details). These options set the principal,